Platonic Philosophy in Ethics, Aesthetics and Politics

PREAMBULE: In our pages

Description in More Details,

Science of Being, and

Pythagorean Man Emulation, we talk

in general terms about the system of values and concepts that are at the foundation of the

EthoPlasìn formation, and that are ba sed on the Pythagorean and Platonic

traditions. To the contrary, the comments of this page have to do more

specifically with the ethics, aesthetics, politics, virtues and values defined

by Plato, in the context of the best possible holistic education to

be given to a

human being in order to make him become the best of citizens. Here we try to be more specific than in other pages, by giving

explanations with reference to the exact sections of Plato's works indicated in

Stephanus Pagination. This is the system of reference and organization

mostly used in modern editions and translations of the 36 works of Plato. His works are divided

into numbers, and each number is divided into equal sections: A, B, C, D and E.

These numbers

and letters are usually put in the margins of the pages of these books. They are

in fact the ones of the Greek texts of

Plato collected in 1578 by the French scholar Henri Estienne, where, in Latin,

Stephanus means Estienne.

sed on the Pythagorean and Platonic

traditions. To the contrary, the comments of this page have to do more

specifically with the ethics, aesthetics, politics, virtues and values defined

by Plato, in the context of the best possible holistic education to

be given to a

human being in order to make him become the best of citizens. Here we try to be more specific than in other pages, by giving

explanations with reference to the exact sections of Plato's works indicated in

Stephanus Pagination. This is the system of reference and organization

mostly used in modern editions and translations of the 36 works of Plato. His works are divided

into numbers, and each number is divided into equal sections: A, B, C, D and E.

These numbers

and letters are usually put in the margins of the pages of these books. They are

in fact the ones of the Greek texts of

Plato collected in 1578 by the French scholar Henri Estienne, where, in Latin,

Stephanus means Estienne.

N.B. When we quote Plato from Republic, we use Politeia, which is, as explained below, its real and best name.

PREMISE:

As a legitimate premise to the study of the ethics, aesthetics and politics of

Plato, we have to say clearly that translating from Ancient-Greek to English, or

to any other modern language, is extremely difficult, sometimes nearly

impossible. Even an institution of as much dignified worthiness as the Cambridge University,

who produced supposedly the English translation of most authority, of Plato,

in its book "Plato - Complete Works",

on which the English translation of the citations of this page is based, often

does not succeed in rendering accurately the real meaning  of the ancient

Greek words. And we will see examples. This is because the

ELL ("Greek") language was just about the most sophisticated

one that

ever existed, with a clear

5000

years of ascertained superiority in front of all other languages, and this is probably why philosophy was 'invented' in

Ancient-Greece, and Ancient-Greek is still taught today in the most serious

schools and universities around the world. Compared to the harmonious complexity and

the subtle nuances of Ancient-Greek, modern languages like English or French are

only simplistic primitive languages that in fact, for the little sophistication

they may have, draw it all from Ancient-Greek.

of the ancient

Greek words. And we will see examples. This is because the

ELL ("Greek") language was just about the most sophisticated

one that

ever existed, with a clear

5000

years of ascertained superiority in front of all other languages, and this is probably why philosophy was 'invented' in

Ancient-Greece, and Ancient-Greek is still taught today in the most serious

schools and universities around the world. Compared to the harmonious complexity and

the subtle nuances of Ancient-Greek, modern languages like English or French are

only simplistic primitive languages that in fact, for the little sophistication

they may have, draw it all from Ancient-Greek.

The most famous example of these

translating difficulties is probably the word "Republic" that is used

worldwide for the name of probably the most famous work of Plato. This gives the

impression that Plato is writing essentially about politics and the form of

government that we know today as a 'Republic'. The real name of the dialogue in

Greek is "Politeia". The word Politeia is a 100 times more subtle than the word

'Republic' in English, a word that is extremely misleading to a newcomer as

to the content to be expected of Plato's 'Republic'. A somewhat closer

translation could be 'Civilization', but even then it would still be much too

deviously restrictive.

'Politeia' means all the essential and best aspects of living humanly and socially in a city in order

to attain the best possible civic environment, or what we call "Civitas" in the context

of the EthoPlasìn Academy. Politeia certainly includes 'Politics',  but it is only

one aspect of 'Politeia', and Plato has another dialogue called precisely

'Politics', or 'Politician' ('Politicus' in Greek, usually translated

very restrictively, and also wrongly again, as "Statesman" in English). Politeia also

includes considerations on laws and legislation, but again this is only another

aspect of 'Politeia', and Plato has yet another dialogue called 'Laws'. Although

the name "Republic" does not reveal it at all, Politeia

is in fact a treatise as much on 'Education' as it is one on politics, laws, and

the ideal government structure and constitution of a 'Republic', and education

in its best meaning of 'holistic education' having to do with the formation of a

man at the 4 levels of the human

Tetractys.

Jean-Jacques

Rousseau even considered Republic the greatest book of pedagogy

and education that was ever written.

And again it has to

do with much more than plain education, rather with a holistic type of

education, for all those who live in the environment of a city, be they farmers,

artisans, warriors, students, teaches or top leaders, and want to make it the best possible civic environment,

each one providing their best possible meritocratic contribution in terms of behavior,

virtue, talent, justice, achievements and dedication.

but it is only

one aspect of 'Politeia', and Plato has another dialogue called precisely

'Politics', or 'Politician' ('Politicus' in Greek, usually translated

very restrictively, and also wrongly again, as "Statesman" in English). Politeia also

includes considerations on laws and legislation, but again this is only another

aspect of 'Politeia', and Plato has yet another dialogue called 'Laws'. Although

the name "Republic" does not reveal it at all, Politeia

is in fact a treatise as much on 'Education' as it is one on politics, laws, and

the ideal government structure and constitution of a 'Republic', and education

in its best meaning of 'holistic education' having to do with the formation of a

man at the 4 levels of the human

Tetractys.

Jean-Jacques

Rousseau even considered Republic the greatest book of pedagogy

and education that was ever written.

And again it has to

do with much more than plain education, rather with a holistic type of

education, for all those who live in the environment of a city, be they farmers,

artisans, warriors, students, teaches or top leaders, and want to make it the best possible civic environment,

each one providing their best possible meritocratic contribution in terms of behavior,

virtue, talent, justice, achievements and dedication.

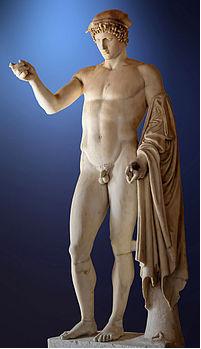

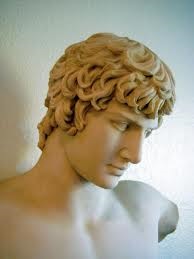

If we were to talk about the translation of the word 'Dimocratia' with the word 'Democracy', we would run into even more serious difficulties as its meaning, in Ancient-Greece, was completely different than the modern word 'democracy', and was much closer to what we could only express today with a complex expression, like possibly a "Direct Participative Meritocracy", at least in as much as we wanted to talk about the ideal form of 'democracy', or 'republic' defined by Plato for his virtual 'Civitas'. And this degree of sophistication in language, along with the 'invention' of philosophy itself at its best, and the creation of education, in a holistic and meritocratic way, and of the first 'universities' of our western civilization, not to mention the development of the spirit of the Olympics (in our context we call it SOS: Social Olympic Spirit) that we still so highly celebrate today, all expressed by the kind of outstandingly handsome men and women that we still admire today in their magnificent sculptures, like the Hermes shown to the right, was taking place some 2500 years ago, when the rest of the western world was literally full of illiterate barbarians cleaning their hands in their hair while devouring their wild preys.

As for Plato himself, who brought the nascent philosophy to an insuperable level, this is particularly amazing if we consider what the English mathematician and philosopher A.N. Whitehead so truly and so well said: "The safest general characterization of the [modern] European philosophical tradition is that it consists only of a series of footnotes to [ancient] Plato". This current of so-called Platonic Philosophy was of course born much before Plato, really from Pythagoras. It then had its best period during a full millennium between Pythagoras and Proclus. This is the period that in our context we often qualify as the period of the 6P Philosophers because the names of the main philosophers of that platonic trend that found its peak with Plato all started with a "P". These include Pythagoras (~550 BC), Plato (~350 BC), Plutarch (~100 AD), Plotinus (~250 AD), Porphyrios (~300 AD) and Proclus (~450 AD). They are distributed in a span of time of about 1000 years, between ~550 BC and ~450 AD. In spite of the immense difficulties mentioned above, we will nevertheless attempt to give the best possible summary of the main concepts of the philosophy of Plato having to do with three fundamental sectors of the EthoPlasìn formation: Ethics, Aesthetics, and Politics.

Particular Difficulty

Regarding the

Concepts of Virtue and Love - The difficulty

about translating the language adequately, mentioned in the premise, is the

reason why so many contemporary authors often give a terrible

misinterpretation of the most difficult concepts of Ancient-Greece

philosophy, of the one of Plato in particular regarding Virtue and Love. In

this particular case, it is a double difficulty: the one about the exact

translation of the words involved, and the one about expressing a

sophisticated culture

and a reality, on the soul side of the human being, that simply does not exist at the moment in our contemporary

world that is too attached to the simplistic concept of "body", regarding

the description of a human being, and not, as it should, to a dualistic

concept of body/soul and the various levels of the human

Tetractys

(also here). For example, the

Cambridge

translation of the words used to name love partners, in talking about

Platonic Love between a mature man and a young man, always uses,

practically systematically, the

simple word "boy", on the side of the younger man, to render the meaning of

various ancient words, or qualifications, like "paidi" ,

"kallos" or "eromenos". This is totally misleading as it seems to point clearly,

and only, at what we see today as a pure male homosexual pedophile

relationship on the part of the older man. This is outrageously simplistic and totally wrong. Translating

with a word like "child" would be a bit better, but also wrong, as it

would seem to still include an aspect of modern sexual pedophilia that did not exist

in the Platonic Love relationship, certainly not in the particular

male-male love relationship theorized by Plato, and that we call today Platonic Love. Using the word

"youth"

as a translation would be quite an

improvement, but still with an imprecise meaning that would also distort the real

sense of a Platonic Love relationship, as "youth" could

refer to both a young man and a young woman, when in fact,

for clear

historical reasons, Platonic Love, as expressed in Plato's works, was

only oriented towards a

"kallos"

young man, certainly not a pre-adolescence

"boy", but rather towards the

handsome young men so widely represented in

the beautiful Greek statues, like the one of Hermes shown further up to the

right. And this relationship had no connotation of homosexuality in the

way we intend it today, but only with the normal and legitimate enjoyment,

with best gratitude, of the purest and most beautiful heart and soul

vibrations of a divinely handsome youth in a state of full grace, and in full

bloom, usually in his third to fourth

Pythagorean

Septennial, between age 15 and 28. This state of

Kallos Beauty however could very well

apply to both young men and young women, as shown in the beautiful

sculptures to the right, of both the male beauty of Hermes Logios

and the female beauty of the Three Graces. Consequently, for the

above reasons, in our translations, regarding the works of Plato

specifically, we have substituted the English word "boy" from the Cambridge book with the

word "beloved", which is much closer to the Greek word

"Eromenos", or

"Paidi" as intended in that ancient philosophical

context. It is still not perfect, but for a perfect

translation we would have to coin a new English word based on Ancient-Greek,

like "Eromenos", and probably also another one,

"Erastis", on the

mature side of the male relationship. There are good hints indicating that a

similar kind of Platonic Love also existed, mutatis mutandis,

between a mature woman and a young woman, but, for the same historical

reasons that made a man's life much more public than a

Cambridge

translation of the words used to name love partners, in talking about

Platonic Love between a mature man and a young man, always uses,

practically systematically, the

simple word "boy", on the side of the younger man, to render the meaning of

various ancient words, or qualifications, like "paidi" ,

"kallos" or "eromenos". This is totally misleading as it seems to point clearly,

and only, at what we see today as a pure male homosexual pedophile

relationship on the part of the older man. This is outrageously simplistic and totally wrong. Translating

with a word like "child" would be a bit better, but also wrong, as it

would seem to still include an aspect of modern sexual pedophilia that did not exist

in the Platonic Love relationship, certainly not in the particular

male-male love relationship theorized by Plato, and that we call today Platonic Love. Using the word

"youth"

as a translation would be quite an

improvement, but still with an imprecise meaning that would also distort the real

sense of a Platonic Love relationship, as "youth" could

refer to both a young man and a young woman, when in fact,

for clear

historical reasons, Platonic Love, as expressed in Plato's works, was

only oriented towards a

"kallos"

young man, certainly not a pre-adolescence

"boy", but rather towards the

handsome young men so widely represented in

the beautiful Greek statues, like the one of Hermes shown further up to the

right. And this relationship had no connotation of homosexuality in the

way we intend it today, but only with the normal and legitimate enjoyment,

with best gratitude, of the purest and most beautiful heart and soul

vibrations of a divinely handsome youth in a state of full grace, and in full

bloom, usually in his third to fourth

Pythagorean

Septennial, between age 15 and 28. This state of

Kallos Beauty however could very well

apply to both young men and young women, as shown in the beautiful

sculptures to the right, of both the male beauty of Hermes Logios

and the female beauty of the Three Graces. Consequently, for the

above reasons, in our translations, regarding the works of Plato

specifically, we have substituted the English word "boy" from the Cambridge book with the

word "beloved", which is much closer to the Greek word

"Eromenos", or

"Paidi" as intended in that ancient philosophical

context. It is still not perfect, but for a perfect

translation we would have to coin a new English word based on Ancient-Greek,

like "Eromenos", and probably also another one,

"Erastis", on the

mature side of the male relationship. There are good hints indicating that a

similar kind of Platonic Love also existed, mutatis mutandis,

between a mature woman and a young woman, but, for the same historical

reasons that made a man's life much more public than a woman's life at that

time, this parallel reality never came out in the open, in any piece of

literature of comparable importance, as much as the relationship

between two men as expressed by Plato. Our page on

Rule 3 and EthoPlasìn Love

Life gives more information on these difficult concepts. Another

page addresses more substantially the question of the divine "Kallos

Beauty" involved in a Platonic Love relationship. Another

flagrant example of this difficulty of translation has to do with the word

"Areti" from

Ancient-Greek, which is usually translated quite simplistically with the

English word

"Virtue". The modern word 'virtue' in turn, never renders the full extent of

the real, and full, meaning of "Areti", as there is no perfect equivalent in any

modern language. Virtue, as a modern word, is too closely, and too

exclusively, associated, or identified, with moral values in a religious sense,

and mostly in relation to sex as opposed to all aspects of human life. The word

"Areti" , when referring to a man, meant globally a "Man of

best value", but in a holistic way, at the four levels of

his human

Tetractys

(also here):

the body, the soul, the spirit and the crowning

wisdom. The meaning of the word evolved in the centuries following Plato.

Machiavelli for example, around

year 1500, used the word "virtu" in a sense much closer to the ancient Greek

meaning than to its contemporary one. This is why the old word "Areti" also gave us the modern prefix

"Aristo", like in "Aristocrat" , or in

Aristarchy (which is

the ultimate form of good government that the PythagorArium is pursuing) that, in its original

ancient meaning, meant really

the most valuable of man, because of his excellence and virtue in his

overall personal and civic behavior and performance. To the contrary, in its current sense, the

word 'Aristocrat' has often a

rather simplistic and derogatory meaning of someone enjoying unmerited privileges because of

noble origin or rich family descent. Fortunately this is not the case with

the word Aristarchy.

woman's life at that

time, this parallel reality never came out in the open, in any piece of

literature of comparable importance, as much as the relationship

between two men as expressed by Plato. Our page on

Rule 3 and EthoPlasìn Love

Life gives more information on these difficult concepts. Another

page addresses more substantially the question of the divine "Kallos

Beauty" involved in a Platonic Love relationship. Another

flagrant example of this difficulty of translation has to do with the word

"Areti" from

Ancient-Greek, which is usually translated quite simplistically with the

English word

"Virtue". The modern word 'virtue' in turn, never renders the full extent of

the real, and full, meaning of "Areti", as there is no perfect equivalent in any

modern language. Virtue, as a modern word, is too closely, and too

exclusively, associated, or identified, with moral values in a religious sense,

and mostly in relation to sex as opposed to all aspects of human life. The word

"Areti" , when referring to a man, meant globally a "Man of

best value", but in a holistic way, at the four levels of

his human

Tetractys

(also here):

the body, the soul, the spirit and the crowning

wisdom. The meaning of the word evolved in the centuries following Plato.

Machiavelli for example, around

year 1500, used the word "virtu" in a sense much closer to the ancient Greek

meaning than to its contemporary one. This is why the old word "Areti" also gave us the modern prefix

"Aristo", like in "Aristocrat" , or in

Aristarchy (which is

the ultimate form of good government that the PythagorArium is pursuing) that, in its original

ancient meaning, meant really

the most valuable of man, because of his excellence and virtue in his

overall personal and civic behavior and performance. To the contrary, in its current sense, the

word 'Aristocrat' has often a

rather simplistic and derogatory meaning of someone enjoying unmerited privileges because of

noble origin or rich family descent. Fortunately this is not the case with

the word Aristarchy.

Hermes Logios (Hermes Orator), ancient Greek sculpture, is shown further up to the right, as a divine messenger and guide of the souls back to their divine source after the harmonious development of their Pythagorean Tetractys and the acquisition of the necessary Wisdom. It is also a symbol of Platonic Love generated by an incredible human Beauty attaining its kallos perfection from its expression of the metaphysical concept of Good in the platonic Theory Of Ideas.

Three Graces, sculpture of Canova (1819) is shown to the right, as an imitation of ancient Greek copies and a reflection of the related Greek mythology.

More than the Creation of Man, we see here

(painting excerpt to the right) the Pythagorean

co ncept of Man's

Desire to Return to God,

as essentially a divine creature to start with, through the "Know Thyself"

and the holistic and equilibrated formation to perfection at all 4 levels of the

"Human Tetractys". This was expressed

beautifully by Michelangelo, albeit some 2000 years later, at the center of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel,

at the Vatican.

In this painting, it is the man who tends the arm, while God

is only holding his hand in an inviting way.

Michelangelo, from a cultural

point of view, was a Neo-Platonist of clear Pythagorean descent, as shown

by the new style of his painting and his sculpting, both very close to the true Ancient-Greece

standards, as opposed to the diluted Latin Middle-Age standards that just

preceded him. As such, he was

probably sensing, quite sadly, that the remains of the ideal of the virtuous

"Pythagorean Man", aspiring, and tending, to a progressive

perfection, in order to return to God in due time in his best possible

state, was in danger of vanishing

completely from the dominant

culture, even surprisingly in the Christian church decadent environment that was overly

obsessed by external power at that time, instead of by internal, and

consequently also civic, perfection objectives and achievements.

ncept of Man's

Desire to Return to God,

as essentially a divine creature to start with, through the "Know Thyself"

and the holistic and equilibrated formation to perfection at all 4 levels of the

"Human Tetractys". This was expressed

beautifully by Michelangelo, albeit some 2000 years later, at the center of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel,

at the Vatican.

In this painting, it is the man who tends the arm, while God

is only holding his hand in an inviting way.

Michelangelo, from a cultural

point of view, was a Neo-Platonist of clear Pythagorean descent, as shown

by the new style of his painting and his sculpting, both very close to the true Ancient-Greece

standards, as opposed to the diluted Latin Middle-Age standards that just

preceded him. As such, he was

probably sensing, quite sadly, that the remains of the ideal of the virtuous

"Pythagorean Man", aspiring, and tending, to a progressive

perfection, in order to return to God in due time in his best possible

state, was in danger of vanishing

completely from the dominant

culture, even surprisingly in the Christian church decadent environment that was overly

obsessed by external power at that time, instead of by internal, and

consequently also civic, perfection objectives and achievements.

Michelangelo's painting is also a symbol of the virtuous man

tending to return to the Beauty and the Good of its original

divine nature through the holistic force of Eros that we explain

further down, as a force that "binds fast the all to all"

[Symposium 202E].

Virtue as Order and Harmony - As said explicitly in Gorgias [506DE-508A], not only man, but all things have virtue if they fulfill orderly the role that makes them being good: "Surely we are virtuous, both we and everything else that is good, when some excellence has come to be present in us". In this way we can talk about the "virtue" of an eye, or of a violin, for their perfect performance rendering, or the virtue of the cosmos sustained by a "just measure" [συμμετρον]. To the contrary, the lack of such orderly behavior reflects a non-virtuous, or a vicious, attribute. In Politeia [352D-353E] Plato says: "The function of each thing is what it alone can do, or what it does better than anything else. ... Anything that has a function, performs it well by means of its own peculiar virtue, and badly by means of its vice". Being virtuous means respecting and reflecting the essence of the perfection of the platonic metaphysical Idea at the foundation of each and every thing, which idea itself participates to the idea of Good sitting at the top of the structure of the World of Ideas. And the essence of the idea of virtue, with regards to man, as explained in Protagoras (this whole work of Plato is essentially about virtue and the education to virtue), is the knowledge of the Good and its actuation. And the Good is the "Just Measure" [συμμετρον] of all things, including the cosmos as a whole. Virtue is thus the mediation between the lack and the excess, that is the "Just Measure" expressing the Good.

The 4 Cardinal

Virtues - These are: Temperance, Fortitude, Prudence and

Justice, as shown in a graphical representation to the left.

As seen briefly in our

Description page, Plato associated closely the 4 cardinal virtues

with the 4 corresponding social classes of the city, described in the Republic, and

with the 4 corresponding faculties of man on the basis of the human

Tetractys

(also

here):

Temperance

was associated mainly with the producing class, the farmers and craftsmen,

and with the animal appetites of the human body; It relates mainly to the lowest part of the

body, the sexual organs and the digestive system;

Fortitude

(or Courage) was associated mainly with the warrior class and with the

emotional ele ment in man; it relates mainly to the solar plexus and the heart

parts of the body;

Prudence

was associated mainly

with the ruling class of society and with the faculty of reason; it relates mainly to the

highest part of the body, the head;

Justice

really

stands above the social class system, and rules the proper

relationship among the other three cardinal virtues, but mainly in human beings who

have reached the wisdom level of the

Tetractys

(also

here): These associations are

based on the fact that, as seen in our page on

Pythagorean Emulation, the

human being is composed of a

Tetractys,

that is, a tripartite basic entity (Body, Soul and Spirit), crowned by a

fourth part, called Wisdom. In

other words, each part of the Tetractys of the human being has its

fundamental virtue, or its Cardinal Virtue: Temperance is related mainly to the

physical Body component of the human being. Fortitude is related

mainly to the

emotional Soul

component. Prudence is related mainly to the rational Spirit component.

Justice is related

to the Wisdom component of the human being, but only where, and only when,

wisdom does

exist in a human being, which is after a long and tenacious work to dominate all the

passions and appetites of the three other basic components.

And this long and

tenacious work to achieve wisdom is precisely the subject of the EthoPlasìn holistic

education. Thus the meaning, and the importance, of the famous "Know

Thyself" concept dominating the whole of the

philosophy of Ancient-Greece and the holistic formation of the EthoPlasìn

Academy. Thus the fundamental difference between

Ancient-Greece philosophy (the founders of Philosophy), and modern

philosophy: the former was first and foremost

a holistic "Way of Being", as opposed to

only a "Way of Understanding", like modern philosophy has reduced

itself being in the last few centuries. As hinted in the first section

of our Home page,

Ancient-Greece philosophy was both aspects,

in a perfectly integrated and harmonious way. The essential missing part, in

modern philosophy, is the reason why there is a need to return to ancient

philosophy, as it was created by its inventors, if we want to use it

properly as the base of best holistic education. Be it clear that many institutions (like

Freemasonry) and religions (like the Catholic Church) have attempted to

steal, or copy, this system of platonic values, the cardinal virtues in

particular, and to adapt them to their own purposes, distorting them

substantially on the way, but the original definition, and

the establishment of the essence of these values is the platonic one, and the only valid one. It is thus the

only one that EthoPlasìn will use in its philosophy and its corresponding holistic formation process. Again,

in

this holistic formation, Temperance is associated to the

physical part of the

Tetractys,

whose passions have to be kept under the good control of the higher parts,

through the cardinal virtue of Temperance [Politeia IV,430E-431A].

Fortitude plays a similar role with the

emotional part of the

Tetractys

[Politeia IV, 429A]. Prudence intervenes similarly at the

highest level of the rational part of the

Tetractys

[Politeia VI-VII]. Finally, Justice ensures that the 3

previous parts function in a perfectly balanced way, in the "Just

Measure", at the level of the spiritual part

(Wisdom) of the

Tetractys

[Politeia IV, 443CE]: "A man who is just does not allow any

part of himself to do the work of another part, or allow the various classes

within him to meddle with each other. He regulates well what is really his

own, and rules himself. He puts himself in order, is his own friend, and

harmonizes the three parts of himself like three limiting notes in a musical

scale, high, low and middle. He binds together those parts and any others

there may be in between, and from having been many things

he becomes

entirely one, moderate and harmonious. Only then does he act.

ment in man; it relates mainly to the solar plexus and the heart

parts of the body;

Prudence

was associated mainly

with the ruling class of society and with the faculty of reason; it relates mainly to the

highest part of the body, the head;

Justice

really

stands above the social class system, and rules the proper

relationship among the other three cardinal virtues, but mainly in human beings who

have reached the wisdom level of the

Tetractys

(also

here): These associations are

based on the fact that, as seen in our page on

Pythagorean Emulation, the

human being is composed of a

Tetractys,

that is, a tripartite basic entity (Body, Soul and Spirit), crowned by a

fourth part, called Wisdom. In

other words, each part of the Tetractys of the human being has its

fundamental virtue, or its Cardinal Virtue: Temperance is related mainly to the

physical Body component of the human being. Fortitude is related

mainly to the

emotional Soul

component. Prudence is related mainly to the rational Spirit component.

Justice is related

to the Wisdom component of the human being, but only where, and only when,

wisdom does

exist in a human being, which is after a long and tenacious work to dominate all the

passions and appetites of the three other basic components.

And this long and

tenacious work to achieve wisdom is precisely the subject of the EthoPlasìn holistic

education. Thus the meaning, and the importance, of the famous "Know

Thyself" concept dominating the whole of the

philosophy of Ancient-Greece and the holistic formation of the EthoPlasìn

Academy. Thus the fundamental difference between

Ancient-Greece philosophy (the founders of Philosophy), and modern

philosophy: the former was first and foremost

a holistic "Way of Being", as opposed to

only a "Way of Understanding", like modern philosophy has reduced

itself being in the last few centuries. As hinted in the first section

of our Home page,

Ancient-Greece philosophy was both aspects,

in a perfectly integrated and harmonious way. The essential missing part, in

modern philosophy, is the reason why there is a need to return to ancient

philosophy, as it was created by its inventors, if we want to use it

properly as the base of best holistic education. Be it clear that many institutions (like

Freemasonry) and religions (like the Catholic Church) have attempted to

steal, or copy, this system of platonic values, the cardinal virtues in

particular, and to adapt them to their own purposes, distorting them

substantially on the way, but the original definition, and

the establishment of the essence of these values is the platonic one, and the only valid one. It is thus the

only one that EthoPlasìn will use in its philosophy and its corresponding holistic formation process. Again,

in

this holistic formation, Temperance is associated to the

physical part of the

Tetractys,

whose passions have to be kept under the good control of the higher parts,

through the cardinal virtue of Temperance [Politeia IV,430E-431A].

Fortitude plays a similar role with the

emotional part of the

Tetractys

[Politeia IV, 429A]. Prudence intervenes similarly at the

highest level of the rational part of the

Tetractys

[Politeia VI-VII]. Finally, Justice ensures that the 3

previous parts function in a perfectly balanced way, in the "Just

Measure", at the level of the spiritual part

(Wisdom) of the

Tetractys

[Politeia IV, 443CE]: "A man who is just does not allow any

part of himself to do the work of another part, or allow the various classes

within him to meddle with each other. He regulates well what is really his

own, and rules himself. He puts himself in order, is his own friend, and

harmonizes the three parts of himself like three limiting notes in a musical

scale, high, low and middle. He binds together those parts and any others

there may be in between, and from having been many things

he becomes

entirely one, moderate and harmonious. Only then does he act. And when he does anything, whether acquiring wealth, taking care of his

body, engaging in politics, or in private contracts, in all of these, he

believes that the action is just and fine that preserves this inner harmony

and helps achieve it, and calls it so, and regards as

wisdom the knowledge that oversees such

actions".

And when he does anything, whether acquiring wealth, taking care of his

body, engaging in politics, or in private contracts, in all of these, he

believes that the action is just and fine that preserves this inner harmony

and helps achieve it, and calls it so, and regards as

wisdom the knowledge that oversees such

actions".

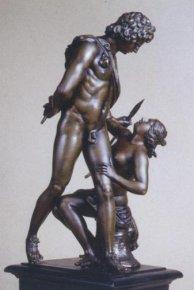

The "Victory on the Minotaur" shown to the right. (as well represented by the beautiful sculpture of Antonio Canova, completed in 1782, and now the property of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London). Theseus exterminates the minotaur of the uncontrolled human passions (a monster represented with the body of a man, and the head of a bull in this case) and, by the same self-mastering operation, finds the rope (running clearly and symbolically from under the dead minotaur, and passing under the right foot of Theseus on the sculpture, indicating the 'right' direction) that will lead him out of the labyrinth, or out of the Platonic Cavern, that is out to the Apollonian Light of the best possible type of personal and civic life.

Virtue as Health and Happiness - In ancient philosophy, virtue is conceived as the health of the overall soul [υγιεια τε τισ ψυχης] intended as the harmony of the 4 parts of the Tetractys (also here), including of course the body [Politeia IV,444CE]. The fundamental precept of the platonic philosophy is that man has to conduct a life in a "Just Measure" [συμμετρον] in order to render all things good and beautiful as much as possible. Plato is very explicit about this in his Timaeus [87D]: "In determining health or disease, or virtue and vice, no proportion, or lack of it, is more important than that between soul and body"... "For both these conditions [health and disease], there is in fact one way to preserve oneself, and that is not to exercise the soul without exercising the body, nor the body without the soul, so that each may be balanced by the other, and so be sound" [Timaeus 88B]... "We should also avoid drugs as, when you try to wipe disease out before they have run their due course of soul equilibrium, the mild diseases are liable to get severe, and the occasional one frequent" [Timaeus 89C]. The highest part of the soul is the Spirit, as our divine guide, and "it resides at the top part of our bodies; it raises us up away from the earth and toward what is akin to us in heaven; For it is from heaven, the place from which our souls were originally born, that the divine part suspends our head, i.e. our root, and so keeps our whole body erect. So if a man has become absorbed in his appetites or his ambitions, and takes great pains to further them, all his thoughts are bound to become sick and merely mortal. And so far as it is at all possible for a man to become thoroughly mortal, he cannot help but fully succeed in this, seeing that he has cultivated his mortality all along. On the other hand, if a man has seriously devoted himself to virtue, to the love of learning, and to true wisdom, if he has exercised these virtuous aspects of himself above all, then there is absolutely no way that his thoughts can fail to be sane, immortal and divine, should Truth become within his grasp. And to the extent that human nature can partake of immortality, he can in no way fail to achieve this: constantly caring for his divine part as he does, keeping well-ordered the guiding spirit that lives within him, he must indeed be also supremely happy" [Timaeus 90ABC]. In short: "A fit body does not, by its own virtue, make the soul good, but, instead, the opposite is true: a good soul, by its own virtue, can make the body as good as possible" [Politeia 403D]. Achieving these levels of virtue, health, wisdom and happiness, is really achieving the Victory on the Minotaur (sculpture of Canova to the right) that we talk about in our home page, and attaining the type of holistic education promoted by the EthoPlasìn Academy.

A Dualistic Conception of Man

and its Paradoxes - For Plato, a man is clearly,

and definitely, a dualistic entity composed of an eternal soul, or rather

immortal once created, but living in a

body for only a definite period of time. The body is in fact like a temporary

prison, even the grave of the soul as, like Euripides once said:

"who knows

whether being alive is being dead and being dead is being alive" [Gorgias

492A]. After what we call death, the soul is liberated and starts living

freely its best life according to its real spiritual nature. All the ethics of Plato

are conditioned by this dualistic conception that he, for the first time in

the history of humanity, brought to light. This brings in a couple of

paradoxes that are difficult to accept in our contemporary world.

The first paradox is that the soul has t he

role to dominate the body entirely, to the point of not being affected in

any way negatively, if and when "its death", or rather the death of its

temporary body, comes to happen. The soul has to have complete independence from, or

certainly over, the body, in the meantime. The death

of the body is only the liberation of the soul from its "oyster shell"

[Phaedrus 250C]. In

the mean time the soul keeps full control of the body (like the beautiful

Enioxos symbol of the sculpture of

the charioteer to the left), based on the philosophy of the

Delphic

"Know

Thyself". As expressed in Phaedo [67A], "while we live, we shall be closest to knowledge if we refrain as much as

possible from association with the body and do not join with it more than we

must, if we are not infected with its nature, but purify ourselves from it

until the god himself frees us [through "death"]. In this way we shall escape the

contamination of the body's folly; in this way we shall be likely to be in

the company of people of the same kind, and by our own efforts we shall know

all that is pure, which is presumably the Truth, for

it is not permitted to

the impure to attain the pure". Again, Plato reinforces the concept in

Politeia [403D]: "A fit body does not by its own virtue make the soul

good, but, instead, the opposite is true: a good soul by its own virtue

makes the body as good as possible". The human soul is created by the

"Demiurgos", but once created, it is immortal. Its cycles of reincarnation

exist only to allow it to exercise its freewill, participate in this way into the

development of the creation as a

co-creator, and eventually return to a life

of happy communion with its creator.

The

second paradox has to do with the

need of the soul to flee from the life and from the world of the body, as much as

possible, during life, and as soon as possible, at the time of death, after

having accomplished as best as possible its contribution and

Mission of

Co-creation, during its earthly life. This is why evil always exists in

this world, in order to give the soul a chance to pursue the Good through

the best use of its freewill. Theatetus [176AB] speaks very clearly in this

regard: "That is why a man should make all haste to escape from earth to

heaven; and escape means becoming as like God as possible; and a man becomes

like God when he becomes just and pious, with understanding". In the

overall process, during his lifetime, the soul has to keep itself as similar

as God as possible in order to achieve this objective and its happiness. In

Laws [716E] we find further insistence on this duty of the human soul:

"If

a good man keeps the gods constant company in his prayers, this will be the

best and noblest policy he can follow; it is the conduct that fits his

character as nothing else can, and it is the most effective way of achieving

a happy life. But if the wicked man does it, the results are bound to be

just the opposite. Whereas the good man's soul is clean, the wicked man's

soul is polluted, and it is never right for a good man, or for God, to receive

gifts from unclean hands, which means that even if impious people do lavish

a lot of attention on the gods, they are wasting their time, whereas the

trouble taken by the pious man is very much in season". These two

paradoxes have a clear common meaning. To flee from the body means to flee

from the evil aspects of the body through virtue and knowledge. To flee from

this earthly life means to flee from the the moral evil of this world, also

through virtue and knowledge, and through the application of the great

principle of the Just Measure [συμμετρον] of order and harmony seen

at the beginning of this page.

he

role to dominate the body entirely, to the point of not being affected in

any way negatively, if and when "its death", or rather the death of its

temporary body, comes to happen. The soul has to have complete independence from, or

certainly over, the body, in the meantime. The death

of the body is only the liberation of the soul from its "oyster shell"

[Phaedrus 250C]. In

the mean time the soul keeps full control of the body (like the beautiful

Enioxos symbol of the sculpture of

the charioteer to the left), based on the philosophy of the

Delphic

"Know

Thyself". As expressed in Phaedo [67A], "while we live, we shall be closest to knowledge if we refrain as much as

possible from association with the body and do not join with it more than we

must, if we are not infected with its nature, but purify ourselves from it

until the god himself frees us [through "death"]. In this way we shall escape the

contamination of the body's folly; in this way we shall be likely to be in

the company of people of the same kind, and by our own efforts we shall know

all that is pure, which is presumably the Truth, for

it is not permitted to

the impure to attain the pure". Again, Plato reinforces the concept in

Politeia [403D]: "A fit body does not by its own virtue make the soul

good, but, instead, the opposite is true: a good soul by its own virtue

makes the body as good as possible". The human soul is created by the

"Demiurgos", but once created, it is immortal. Its cycles of reincarnation

exist only to allow it to exercise its freewill, participate in this way into the

development of the creation as a

co-creator, and eventually return to a life

of happy communion with its creator.

The

second paradox has to do with the

need of the soul to flee from the life and from the world of the body, as much as

possible, during life, and as soon as possible, at the time of death, after

having accomplished as best as possible its contribution and

Mission of

Co-creation, during its earthly life. This is why evil always exists in

this world, in order to give the soul a chance to pursue the Good through

the best use of its freewill. Theatetus [176AB] speaks very clearly in this

regard: "That is why a man should make all haste to escape from earth to

heaven; and escape means becoming as like God as possible; and a man becomes

like God when he becomes just and pious, with understanding". In the

overall process, during his lifetime, the soul has to keep itself as similar

as God as possible in order to achieve this objective and its happiness. In

Laws [716E] we find further insistence on this duty of the human soul:

"If

a good man keeps the gods constant company in his prayers, this will be the

best and noblest policy he can follow; it is the conduct that fits his

character as nothing else can, and it is the most effective way of achieving

a happy life. But if the wicked man does it, the results are bound to be

just the opposite. Whereas the good man's soul is clean, the wicked man's

soul is polluted, and it is never right for a good man, or for God, to receive

gifts from unclean hands, which means that even if impious people do lavish

a lot of attention on the gods, they are wasting their time, whereas the

trouble taken by the pious man is very much in season". These two

paradoxes have a clear common meaning. To flee from the body means to flee

from the evil aspects of the body through virtue and knowledge. To flee from

this earthly life means to flee from the the moral evil of this world, also

through virtue and knowledge, and through the application of the great

principle of the Just Measure [συμμετρον] of order and harmony seen

at the beginning of this page.

A New Table of

Values Caused by Metaphysics - Up until Socrates and Plato, humanity

had never made a real distinction in its thinking between body and soul: it

was one and the same thing, as a human being.

Socrates was the real discoverer of the soul as a separate entity of the

human being. And this separate entity became the main, and most essential,

component of the conception of a human being. Socrates however has never written anything. He

speaks only through the writings of Plato, and nearly only through these writings.

Consequently, it might very well be that what Socrates says

about the soul is really

Plato's discovery and thinking. Who of the two had first this beautiful intuition of a

clear distinction is not really

important. In practice however, it is certainly Plato who brings this intuition

to its full metaphysical development. On the basis of Plato's Theory of

Ideas, or Theory of Forms, in the same way that a man is composed of a "divine" met aphysical and

invisible immortal component (the soul), and of a visible mortal physical one (the body), everything

else in our world has a physical component (the visible thing) that

corresponds to its metaphysical (and invisible) model, or form (the invisible

Idea founding it, or giving it its nature and functions). This is the

historical passage from physics to metaphysics, that

happened then, for the

first time, in the history of humanity, and a passage that is really the

foundation of what we now call Philosophy. By the same token, this major and fundamental

achievement in human thinking, along with the new dualistic conception of man,

is, inevitably, as a consequence, the source of an entirely new Table of

Values for the human being, like the "limiting notes of a musical

scale"

[Politeia IV, 443D], regarding the height and quality of his living and his social behavior. In

that table, the values of the soul become more important

than the values of the body, or at least have a priority in founding the

quality, and real Beauty, of a human being. In the same manner, the values for

judging the quality or the beauty of a physical thing have a direct

reference to its degree of correspondence to the Form of the Idea behind

this visible thing. All this led to the establishment of a real Table

of Values, created by the newly-born philosophy, that will influence the

rest of the history of humanity and its ethics until today. At the top level

of the table, there were the Spiritual Values, the ones of the soul as the

most important part of the human being, corresponding essentially to the top

level of the

Tetractys

(also

here),

and that we can summarize in two concepts: Wisdom and Justice. At the middle

level there were the Vital Values, corresponding to the three lower levels of the

Tetractys, and that can be summarized with the names of the

so-called Cardinal

Virtues of Prudence, Fortitude and Temperance. At the bottom level, there were

the Physical Values, corresponding to the degree of goodness of the

practical things required for personal and social living, like money,

personal belongings and what constitutes what we normally consider wealth. In

this scale, lower values are really good values only if subordinated to

a higher level. In Laws [726A-727A] Plato is quite explicit about this

table of values: "There are two elements that make up the whole of every

man. One [soul] is stronger and superior, and acts as a master; the other

[body], which is

the weaker and inferior, is a slave; and so a man must always respect the

master in him in preference to the slave. Next after the gods, a man

must honor his soul".

aphysical and

invisible immortal component (the soul), and of a visible mortal physical one (the body), everything

else in our world has a physical component (the visible thing) that

corresponds to its metaphysical (and invisible) model, or form (the invisible

Idea founding it, or giving it its nature and functions). This is the

historical passage from physics to metaphysics, that

happened then, for the

first time, in the history of humanity, and a passage that is really the

foundation of what we now call Philosophy. By the same token, this major and fundamental

achievement in human thinking, along with the new dualistic conception of man,

is, inevitably, as a consequence, the source of an entirely new Table of

Values for the human being, like the "limiting notes of a musical

scale"

[Politeia IV, 443D], regarding the height and quality of his living and his social behavior. In

that table, the values of the soul become more important

than the values of the body, or at least have a priority in founding the

quality, and real Beauty, of a human being. In the same manner, the values for

judging the quality or the beauty of a physical thing have a direct

reference to its degree of correspondence to the Form of the Idea behind

this visible thing. All this led to the establishment of a real Table

of Values, created by the newly-born philosophy, that will influence the

rest of the history of humanity and its ethics until today. At the top level

of the table, there were the Spiritual Values, the ones of the soul as the

most important part of the human being, corresponding essentially to the top

level of the

Tetractys

(also

here),

and that we can summarize in two concepts: Wisdom and Justice. At the middle

level there were the Vital Values, corresponding to the three lower levels of the

Tetractys, and that can be summarized with the names of the

so-called Cardinal

Virtues of Prudence, Fortitude and Temperance. At the bottom level, there were

the Physical Values, corresponding to the degree of goodness of the

practical things required for personal and social living, like money,

personal belongings and what constitutes what we normally consider wealth. In

this scale, lower values are really good values only if subordinated to

a higher level. In Laws [726A-727A] Plato is quite explicit about this

table of values: "There are two elements that make up the whole of every

man. One [soul] is stronger and superior, and acts as a master; the other

[body], which is

the weaker and inferior, is a slave; and so a man must always respect the

master in him in preference to the slave. Next after the gods, a man

must honor his soul".

A Just Appreciation

of Pleasure and Pain - Some of the writings of Plato give the

impression that pleasure is considered very negatively in the new Table of

Values. For example, in Phaedo [83BE] we read the following:

"the soul

of the true philosopher keeps away from pleasures and desires and pains as

far as he can ... as they will cause the greatest and most extreme evil ...

if they tie the soul too much to the body; Every pleasure or pain provides

another nail to rivet the soul to the body and to weld them together. It

makes the soul corporeal, so that it believes th at truth is what the body

says it is". However, Plato makes a distinction between the pleasures

of the three parts of the

Tetractys

(also

here)

of the human being and sees them as a prerogative, more of the soul than of

the body, with the quality of the pleasures being valued on the basis of the

same hierarchy that applies to the four parts of the human

Tetractys

(also

here).

It is really the pleasures of the lowest parts that have to kept under good

control, and avoided if they are to be used blindly or without the

consciousness that they tie the soul too much to the body. In Politeia

[585DE-586DE] Plato says clearly that pleasures can all be enjoyed justly at

certain conditions: "The kinds of pleasures that are concerned with

the care of the body share less in truth, and in being, than those concerned

with the care of the soul. ...Therefore, when the entire soul follows the

philosophic part [the Wisdom, in the

Tetractys], each other part of it

complies to its own function and behaves justly; and as a result, each other

part will enjoy justly its own pleasures, the best and truest pleasures

possible for it". In Philebus [66E-67B], Plato re-dimensions, without

renegading it, the ascetical conception of ethics of Gorgias,

by affirming that a man is both a soul and a body, and cannot live happily

only with the pleasures of one or the other: "The pleasure of reason is far superior to

pleasure of the body and more beneficial for human life. … But both reason and pleasure

have lost any claim that one or the other is, by itself, the Good itself,

since they lack in autonomy, and in the power of self-sufficiency and

perfection". Man has, and needs, a life with a just mixture of pleasures, from

the body, the soul and the spirit, and his life is a good one if the mixture is

right, giving priority to the pleasures of the higher part, and keeping

under control of the higher part the pleasures of the lower parts. These

considerations are reaffirmed in Laws [732D-734E] in a way that could be an

anticipation of the forthcoming Epicureans, where Plato says that, in a good

life, pleasure has to predominate over pain: "Human nature

involves, above all, pleasures, pains, and desires, and no mortal animal

[like man] can

help being hung up in total dependence of these powerful influences. This is

why we should praise the noblest life … because it excels in providing what

we all seek: a predominance of pleasure over pain throughout our lives. … We

have to ask if one condition suits our nature, while another does not, and

weigh the pleasant life against the painful, with that question in mind. …

We want less pain and more pleasure. … We want a life in which pleasures and

pains come frequently and with great intensity, but with pleasure

predominating; one should select a life that will enable him to live as

happily as a man can. … [On the basis of the 4 parts of the

Tetractys,

there are 4 basic types of life:] There is a life of self-control, a

life of courage, a

life of wisdom and a what we can call a life

of overall health; As

opposed to these, we have another 4 lives, the licentious, the cowardly, the

foolish and the diseased. … What we want when we choose between lives is not

a predominance of pain. … The courageous man does better than the coward,

the wise man than the fool; so that, life for life, the former kind, the

restrained, the courageous, the wise and the healthy, is pleasanter than the

cowardly, the foolish, the licentious and the unhealthy. … To sum up, the

life of physical fitness, and spiritual virtue

together, is not only pleasanter

than the life of depravity, but superior in other ways as well: it makes for

beauty, and upright posture, efficiency and a good reputation, so that if a

man lives a life like that, it will make his whole existence infinitely

happier than his opposite number's". These last statements conclude the

prelude of Laws, and the clear indication of the basic principles

on which all national laws should be based on, and on the basis of which all

men should be justly treated, in order to ensure the happiest possible civic

life in a good society. The whole of Laws is an magisterial essay

on ethics, related to the criteria for the establishment of best civic authority,

an ideal

personal virtuous discipline and most legitimate just authority. And

all these concepts are part of the holistic formation provided at the

EthoPlasìn Academy.

at truth is what the body

says it is". However, Plato makes a distinction between the pleasures

of the three parts of the

Tetractys

(also

here)

of the human being and sees them as a prerogative, more of the soul than of

the body, with the quality of the pleasures being valued on the basis of the

same hierarchy that applies to the four parts of the human

Tetractys

(also

here).

It is really the pleasures of the lowest parts that have to kept under good

control, and avoided if they are to be used blindly or without the

consciousness that they tie the soul too much to the body. In Politeia

[585DE-586DE] Plato says clearly that pleasures can all be enjoyed justly at

certain conditions: "The kinds of pleasures that are concerned with

the care of the body share less in truth, and in being, than those concerned

with the care of the soul. ...Therefore, when the entire soul follows the

philosophic part [the Wisdom, in the

Tetractys], each other part of it

complies to its own function and behaves justly; and as a result, each other

part will enjoy justly its own pleasures, the best and truest pleasures

possible for it". In Philebus [66E-67B], Plato re-dimensions, without

renegading it, the ascetical conception of ethics of Gorgias,

by affirming that a man is both a soul and a body, and cannot live happily

only with the pleasures of one or the other: "The pleasure of reason is far superior to

pleasure of the body and more beneficial for human life. … But both reason and pleasure

have lost any claim that one or the other is, by itself, the Good itself,

since they lack in autonomy, and in the power of self-sufficiency and

perfection". Man has, and needs, a life with a just mixture of pleasures, from

the body, the soul and the spirit, and his life is a good one if the mixture is

right, giving priority to the pleasures of the higher part, and keeping

under control of the higher part the pleasures of the lower parts. These

considerations are reaffirmed in Laws [732D-734E] in a way that could be an

anticipation of the forthcoming Epicureans, where Plato says that, in a good

life, pleasure has to predominate over pain: "Human nature

involves, above all, pleasures, pains, and desires, and no mortal animal

[like man] can

help being hung up in total dependence of these powerful influences. This is

why we should praise the noblest life … because it excels in providing what

we all seek: a predominance of pleasure over pain throughout our lives. … We

have to ask if one condition suits our nature, while another does not, and

weigh the pleasant life against the painful, with that question in mind. …

We want less pain and more pleasure. … We want a life in which pleasures and

pains come frequently and with great intensity, but with pleasure

predominating; one should select a life that will enable him to live as

happily as a man can. … [On the basis of the 4 parts of the

Tetractys,

there are 4 basic types of life:] There is a life of self-control, a

life of courage, a

life of wisdom and a what we can call a life

of overall health; As

opposed to these, we have another 4 lives, the licentious, the cowardly, the

foolish and the diseased. … What we want when we choose between lives is not

a predominance of pain. … The courageous man does better than the coward,

the wise man than the fool; so that, life for life, the former kind, the

restrained, the courageous, the wise and the healthy, is pleasanter than the

cowardly, the foolish, the licentious and the unhealthy. … To sum up, the

life of physical fitness, and spiritual virtue

together, is not only pleasanter

than the life of depravity, but superior in other ways as well: it makes for

beauty, and upright posture, efficiency and a good reputation, so that if a

man lives a life like that, it will make his whole existence infinitely

happier than his opposite number's". These last statements conclude the

prelude of Laws, and the clear indication of the basic principles

on which all national laws should be based on, and on the basis of which all

men should be justly treated, in order to ensure the happiest possible civic

life in a good society. The whole of Laws is an magisterial essay

on ethics, related to the criteria for the establishment of best civic authority,

an ideal

personal virtuous discipline and most legitimate just authority. And

all these concepts are part of the holistic formation provided at the

EthoPlasìn Academy.

Soul Purification

to Attain Wisdom - Pythagoras was the first one to talk

openly about the need of the purification of the soul through the

intervention of the highest part of the

Tetractys.

Then Socrates posed firmly the "Cure of the Soul" as the supreme duty of all

human being who want to achieve wisdom and happiness. Plato finally pushes the concept

of purification to its full extent. He affirms, that the purification of the soul is only

achieved fully when, after the long work of the Delphic "Know Thyself",

characterizing a philosophical life, a man's consciousness has finally access to

the metaphysical dimension of the World of Ideas and its leading role in comprehending

and handling both reality in general and human life in particular. By

accessing this high level of consciousness, man is finally "converted" to an

elevated leve l of life that identifies knowledge with virtue, as integrated

in what he calls Wisdom. This is the top level of the

Tetractys

(also

here),

and the

crowning of a so-called "philosophical life", that is the best life

that can lead a human being in its

Mission of Co-Creation. Plato's

Phaedo [69AD] is quite

explicit about all this: "I fear this is not the right exchange to

attain virtue, to exchange pleasures for pleasures, pains for pains, and

fears for fears, the greater for the less, like coins, but that the only

valid currency for which all these things should be exchanged is

Wisdom.

With this, we have real courage and moderation and justice and, in a word,

true virtue, with wisdom, whether pleasures and fears and all such things be

present or absent. When these are exchanged for one another, in separation

from wisdom, such virtue is only an illusory appearance of virtue; … Wisdom

itself is a kind of cleansing, or purification ... and the characteristic of

those who have practiced philosophy the right way". Wisdom, as

the crowning of a good

Tetractys,

and, as such, the leader of all virtues, is thus the key to attaining the most

possible happy human life after a holistic formation like the one provided

by the EthoPlasìn Academy.

l of life that identifies knowledge with virtue, as integrated

in what he calls Wisdom. This is the top level of the

Tetractys

(also

here),

and the

crowning of a so-called "philosophical life", that is the best life

that can lead a human being in its

Mission of Co-Creation. Plato's

Phaedo [69AD] is quite

explicit about all this: "I fear this is not the right exchange to

attain virtue, to exchange pleasures for pleasures, pains for pains, and

fears for fears, the greater for the less, like coins, but that the only

valid currency for which all these things should be exchanged is

Wisdom.

With this, we have real courage and moderation and justice and, in a word,

true virtue, with wisdom, whether pleasures and fears and all such things be

present or absent. When these are exchanged for one another, in separation

from wisdom, such virtue is only an illusory appearance of virtue; … Wisdom

itself is a kind of cleansing, or purification ... and the characteristic of

those who have practiced philosophy the right way". Wisdom, as

the crowning of a good

Tetractys,

and, as such, the leader of all virtues, is thus the key to attaining the most

possible happy human life after a holistic formation like the one provided

by the EthoPlasìn Academy.

The Delphic Tripod to the right. The tripod is the symbol of best stability, even on uneven grounds. The 3 snakes twisted together represent the past, present and future that, in as much as the soul acquires its best Tetractys formation, will support and manifest the best expression of the higher tripod: its 3 legs stand for the first 3 elements of the quaternion of the Pythagorean Tetractys (Body, Soul and Spirit), while its golden color and crowning cup represent wisdom, the fourth element of the quaternion (with its precious leading light), that will bring about the best possible form of human behavior and happiness on beautiful planet Earth

Friendship

- For Plato, real friendship is an ethical question and reality that is also based on the

dualistic and metaphysical dimension of the human being. It has to do with

the natural pursuit of the Good as the top value in his Theory of Ideas.

Friendship is a pure

relationship, different from love, and with no connotation per se of sexual

attraction. Love, or sexual attraction, may well be born from friendship, but they

are then something different, or something additional that does not change

the nature itself of friendship. Real friendship has

nothing

to do with the physical, but only with the metaphysical dimension of

the human being and its natural aspiration to the Good through the best part

of its Tetractys

(also

here).

The best way to explain all this, is maybe to simply let Plato speak in his own words from

his work Lysis

[218C-221E]: "The soul, that which is neither entirely good or entirely

bad itself, is, by the presence of the evil part, a friend of the Good. …

Whoever is a friend, is a friend of someone for the sake of something...

like a sick man is a friend to the doctor… and if he is a friend on account

of disease, it is for the sake of health. It is for the sake of health [the

aspiration to a good thing] that the doctor has received friendship, even if

it is on account of disease [an evil thing to be eliminated]. … So what is

neither entirely good, nor entirely bad [like a human being], is a friend of the

good

on account of what is bad, but for the sake of what is good. … So, somehow,

the friend is friend of its friend for the sake of a friend, on account of

its enemy. … 'Like' has become friend of 'like' in a chain reaction that goes up

in quality

but has to arrive at a first principle which will no longer bring us back to

another friend, something that goes back to the first friend, something for

the sake of which we say that all the rest are friends too. … It is that

first thing which is truly a friend [which is the ontological Good]. … It is

on account of bad that the Good is loved. Without the disease, there is no

need for the medicine. … A thing desires what it is deficient in. … The

deficient is a friend to that in which it is deficient. … But it feels

deficient where something is taken away from it. … something that belongs to

it. So if two persons are friends with each other, in some way they

naturally belong to each other". In other words, friendship is such

only if it is a pursuit of the ontological Good, and when this pursuit is

absent in a relationship, it is not friendship, but something else, at a

lower level, and for the pursuit of lower objectives.

to do with the physical, but only with the metaphysical dimension of

the human being and its natural aspiration to the Good through the best part

of its Tetractys

(also

here).

The best way to explain all this, is maybe to simply let Plato speak in his own words from

his work Lysis

[218C-221E]: "The soul, that which is neither entirely good or entirely

bad itself, is, by the presence of the evil part, a friend of the Good. …

Whoever is a friend, is a friend of someone for the sake of something...

like a sick man is a friend to the doctor… and if he is a friend on account

of disease, it is for the sake of health. It is for the sake of health [the

aspiration to a good thing] that the doctor has received friendship, even if

it is on account of disease [an evil thing to be eliminated]. … So what is

neither entirely good, nor entirely bad [like a human being], is a friend of the

good

on account of what is bad, but for the sake of what is good. … So, somehow,

the friend is friend of its friend for the sake of a friend, on account of

its enemy. … 'Like' has become friend of 'like' in a chain reaction that goes up

in quality

but has to arrive at a first principle which will no longer bring us back to

another friend, something that goes back to the first friend, something for

the sake of which we say that all the rest are friends too. … It is that

first thing which is truly a friend [which is the ontological Good]. … It is

on account of bad that the Good is loved. Without the disease, there is no

need for the medicine. … A thing desires what it is deficient in. … The

deficient is a friend to that in which it is deficient. … But it feels

deficient where something is taken away from it. … something that belongs to

it. So if two persons are friends with each other, in some way they

naturally belong to each other". In other words, friendship is such

only if it is a pursuit of the ontological Good, and when this pursuit is

absent in a relationship, it is not friendship, but something else, at a

lower level, and for the pursuit of lower objectives.

Eros as a Force to

Acquire and Create Immortal Beauty to Attain the Eternal Good

- Eros, or the erotic life of a human being, is also a concept that is very

far from the meaning of the word in our contemporary world. It is also

entirely different from 'Love' as a concept. Like friendship, Eros is also

based on the metaphysical dimension of the human being, and it is why it was

considered a God in ancient Greek philosophy, or a divine-like faculty

acting at the holistic dimension of the

Tetractys

(also here).

Curiously enough, contrary to

its meaning today, Eros has little to do with sex, or at least not with sex

as its main nature or level of action. Like friendship, Eros is first and foremost the

expression of the pursuit

of the Good, but through Beauty this time, and beauty in

all aspects of life, not at

all only the physical beauty of the human body, let alone its purely sexual

faculty. In any case, Eros is tightly linked to the concept of Beauty, but

metaphysical Beauty. For Plato, the beauty of a work of art is "the

imitation of an imitation", that is a level of beauty that is 3 levels

under the real metaphysical Beauty, which is essentially the Idea of Beauty

that is an expression of harmony, order and the just measure, or the

Beauty

at the fundamental level of the "being" that best expresses the Good. This is

the kind of beauty that Greek philosophy called

"Kallos", as

explained in our page on Kallos Beauty.

And Eros is the force that moves the human being to pursue that Beauty, or

the Good that one is missing, in all aspects of live, and at levels higher

and higher, up to the level of contemplation. At that level, Eros becomes

Ecstasy, an ecstasy that is very close to the religious, or rather the

mystical ecstasy of some saints, like the one expressed in the

beautiful and famous sculpture of Bernini, "The Ecstasy of Saint

Theresa", in the Basilica of Santa Maria della Vittoria, in Rome,